Inner City Reforestation in Utrecht and the G/Local Amazon; Psychogeography is involved.

Posts tonen met het label art. Alle posts tonen

Posts tonen met het label art. Alle posts tonen

zondag 9 maart 2014

The little man of Willemstad

Been bending over this today in the Dutch Royal Museum of Antiquities, its an oak figure with a C14 age of 5300 to 5000 years before present. Its 12.5 cm high and fits in the hand. The image does no justice to seeing the object in front of you. This Fibula was another favourite.

vrijdag 26 april 2013

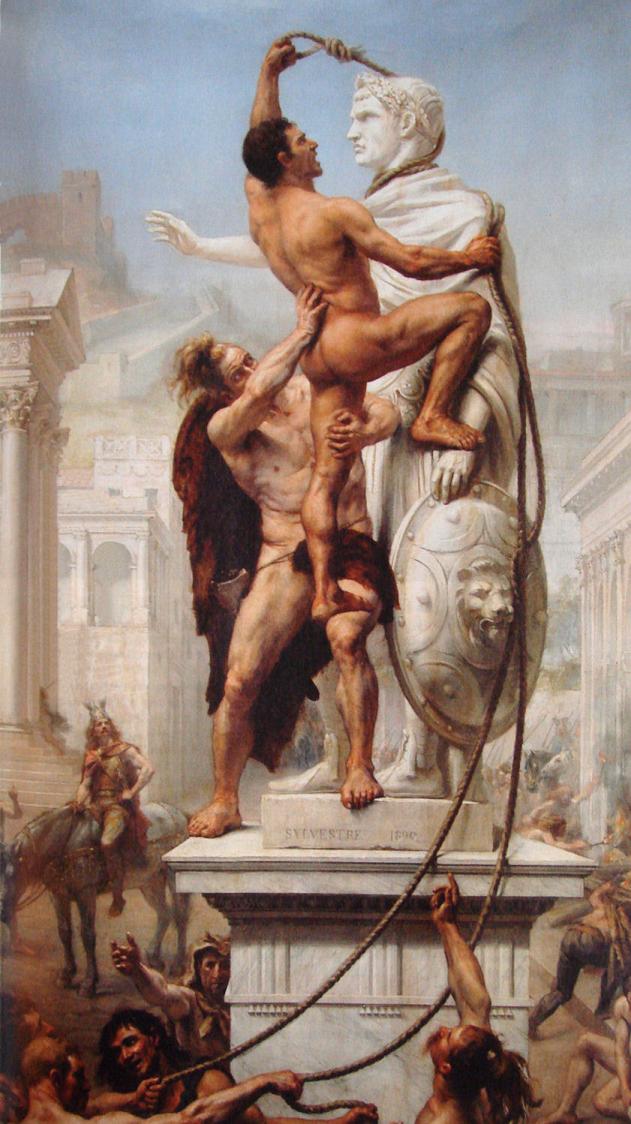

Hate crime against the barbarians

Have been greatly enjoying Waldemar Januszczak' The Dark Ages. In the episode on the barbarians he begins by showing the above "Sack of Rome by the Visigoths on 24 August 410" painted by JN Sylvestre in 1890. It's has all the outrageous drama of a hate-crime against a vernacular culture. Also: the Goths were not naked, they were in fact the ones inventing the trousers!

zaterdag 9 juni 2012

Tuniit art in the medieval warm period

| ||

Robert McGhee's 'The last imaginary place' surveys the human history of the Arctic north, showing that people without history (to use the phrase by Eric Wolf, another brilliant book I am reading at the moment ) do have a complex, living past. The history of the now extinct Tuniit or Dorset culture is worth your attention, I was particularly intrigued by the following quote that links the number of artistic artefacts with the despair brought about by climatic change:

The art of the Dorset people is so varied and intricate that it allows a glimpse of the spirit-world known to these ancient hunters, a world resembling in many ways that of the other northern shamanic peoples, yet unique to this society that developed in the relative isolation of Arctic North America over a period of almost five millennia. Their art also appears to foreshadow the end of Tuniit society. In the last few centuries of their existence, between about AD 1000 and 1500, Dorset artists produced an ever-increasing number of amulets and objects of shamanic use. This was also the period of increasing stress on the societies to which the artists belonged. In these centuries the Northern hemisphere was subject to warming climatic conditions that are known in Europe as the Medieval Warm Period. To Tuniit hunters who seem to have been adapted to primarily to hunting on land and sea-ice, the unexpected appearance of open water during early summer or a delay in the expected freezing of autumn seas would have brought hardship and often disaster.

At the same time the Viking were using the warmer conditions to find their way to Greenland and beyond. Image:"Miniature ivory mask representing a humanface, Dorset, Devon Island, Nunavut, circa 1700 B.C." Possibly it's a portrait, they lines may represent tattooing? A humbling face.

woensdag 25 januari 2012

How the invaded recorded the invaders

The earlier post of the Inuit carving of a Viking reminded my of Julia Blackburn's 1979 book 'The White Men, the first response of aboriginal peoples to the white men'. It's a collection of drawings, artefact and stories that remind us that just as 'they' entered our history, we entered theirs. The book begins with an excellent foreword by Canadian anthropologist Edmund Carpenter and continues with a zillion documents from Africa, North America, Oceania and Indonesia illustrated with artworks. The texts are a bit much for me but the images are stunningly fascinating as you can see for yourself in the small sample below.

|

| West African legend says that the white men came from a hole in the ground, a mud sculpture from Nigeria. |

|

| Fully rigged ship on a New Caledonian bamboo pole (1850ties). |

|

| Portrait of a missionary from the Western Congo. (1930-40ties) |

|

| Mask of a sailor from the West Coast of Africa around 1900. |

|

| Nicobar Island scare-devil in the form of a policeman. |

|

| Cave Painting in Arnhem Land showing the recent surge of European visitors. (1940ties) |

|

| A 1850ties Eskimo seal skin showing whales, ships and people. A map? |

|

| A Dutch couple depicted by a South African bushman in the mid 1850ties. |

|

| Papua New Guinean Christ after WWII |

|

| Brass bracelet made by the Dogon in Mali. |

zondag 25 december 2011

The stamp-sized Chico Mendez memorial garden

Here is what I found when I went to the local Rooie Rat (Red Rat) bookstore this week: Thing 001359 (Chico Mendez Mural Garden), a micro garden exhibit part of the excellent and ongoing 'The Grand Domestic Revolution' series initiated by Casco. I am wondering though if I am the only one to see the irony: you begin with Chico Mendez a Brazillian rubber tapper and union leader who gets murdered for his efforts to preserve the Amazon rainforest. After his death the man gets honoured with a New York community garden that was evicted. This garden is remembered as an avant-gardening classic and used as a source for the greening of cities everywhere, in this case it inspires a model of itself with a few unhealthy (not to mention unhappy) looking plants in a mushy bookstore in Utrecht. Is that the diminutive value of borrowed aura? Anyway: cryptoforestry salutes all things and all people that bring the Amazon to Utrecht. Hurrah!

zaterdag 24 september 2011

"Empty space creates a richly filled time"

|

| Melancholy and Mystery of a Street, Giorgio de Chirico, 1914 |

Ivan Chtcheglov's 1953 'Formulary for a New Urbanism' is everybody's favourite example of Situationist psychogeographix loonie prose. It certainly is one the most accessible and likeable works in the corpus from which many people have quoted and after which the Manchester Hacienda was named. I have always been baffled with Debord upping jaded, sentimental Claude Lorrain and Chtcheglov here, while mentioning Lorrain, recommends clean, graphic and controlled De Chirico as his favourite place where to find inspiration for the construction of the emotively charged spaces of the future.

De Chirico remains one of the most remarkable architectural precursors. He was grappling with the problems of absences and presences in time and space.

We know that an object that is not consciously noticed at the time of a first visit can, by its absence during subsequent visits, provoke an indefinable impression: as a result of this sighting backward in time, the absence of the object becomes a presence one can feel. More precisely: although the quality of the impression generally remains indefinite, it nevertheless varies with the nature of the removed object and the importance accorded it by the visitor, ranging from serene joy to terror. (It is of no particular significance that in this specific case memory is the vehicle of these feelings; I only selected this example for its convenience.)

In De Chirico’s paintings (during his Arcade period) an empty space creates a richly filled time. It is easy to imagine the fantastic future possibilities of such architecture and its influence on the masses. We can have nothing but contempt for a century that relegates such blueprints to its so-called museums.

maandag 18 juli 2011

Fluxus and the forest

After the urban cryptoforest revolt of 2020 forestry will become art and art will be on the dump heap of history, until then we need to do with the mediocre. Bengt Af Klinktberg's (born 1938) Fluxus pieces from the 1960/70ties used:

"The forest as a marionette theatre. I read in my encyclopaedia: a theatre with jointed puppets which by means of threads can be made to imitate the movements of human beings. The marionette is generally around 50 centimetres tall and appears in a theatre reduced to the same scale. Why not, for once, a really large and airy stage? Perched in two treetops my brother-in-law Olle and I pull and release ropes. Between us is the forest diver, performing a slow dance with grave and waving movements, like a huge, reluctant jumping-jack, insulted by our proceedings but still not quite negative... "

As quoted from 'The Forest Diver' included in a 1974 issue of Alcheringa while the Fluxus Performance Workbook (PDF-link) includes Seven Forest Events from his hand.

Seven Forest Events (1966)

Forest Event Number One [Winter]

Walk out into a forest when it is winter and decorate all the spruces with burning candles, flags, apples, glass balls, tinsel strings.

Forest Event Number Two

Walk out into a forest and wrap some drab trees, or yourself, in tinsel.

Forest Event Number Three

Climb up a treetop with a saw. Saw through the tree-trunk from the top right down to the root.

Forest Event Number Four [Danger Music for Henning Christiansen]

Climb up into a tree. Saw off the branch you sit upon.

Forest Event Number Five [The Lumberjack' and Piker's Union]

Charlotte Moorman exchanged the sand-paper for a saw, but using that sawing technique she would have been sacked Lumberjack' and Piker's Union.

Forest Event Number Six

Walk out of your house. Walk to the forest. Walk into the forest.

Forest Event Number Seven

When you walk into a forest, don't forget to knock.

woensdag 23 maart 2011

Time Landscape [fence=frame]

Just because Jane Jacobsen supported it does not mean it is a good idea.

"Time Landscape" (1978) is a prominently located land art piece by Alan Sonfist recreating a pre-Columbian Manhattan forest. Or as Michael Pollen describes it:

A Pedestrian standing at the corner of Houston Street and La Guardia Place in Manhattan might think that the wilderness had reclaimed a tiny corner of the city’s grid here. Ten years ago, an environmental artist persuaded the city to allow him to create on this site a “Time Landscape” showing New Yorkers what Manhattan looked like before the white man arrived. On a small hummock he planted oak, hickory, maples, junipers, and sassafras, and they’ve grown up to form a nearly impenetrable tangle, which is protected from New Yorkers by a steel fence now thickly embroidered with vines. It’s exactly the sort of “garden” of which Emerson and Thoreau would have approved—for the very reason that it’s not a garden.

A project like the Time Landscape is not so much of interest for itself but for what people make of it over time. A garden, even an anti-garden, is just a place to be in, a forest, even a cryptoforest, is a state of mind, a psychological condition that attracts shrinks and social health workers and the rest of the Cuckoo Club.

The Village Voice website has a 2007 article on a volunteer mass clean-up that sought to eradicate invasive (non-native) species as well as the creation of sight-lines to prevent people from hiding in the bushes.

"Although a chain-link fence encloses the area and entrance is by key, there is a hole in the fence and it is possible to climb over the waist-high barrier."

The fence is not to frame the art but to keep art lovers outside of it.

Nonnative plants and weeds have spread to the garden, and the sight of morning glories clinging to the fence troubled many.

“The concept was to have native species,” said Tobi Bergman, chairperson of the C.B. 2 Parks Committee, in a phone interview before the cleanup. “But there is a reason we call them invasive species: They have no natural enemies.”

Sonfist dismissed these criticisms.

“This is an open lab, not an enclosed landscape,” he said. “The intention was never to keep out all nonnative species, but rather to see how they come into the space with time.”

The Time Landscape is a hegemonic plant community that refuses to interact, like a silent Indian who is the last of his tribe and who refuses to engage with his own feelings or those of outsiders and instead just waits and waits and waits.

In terms of PR the fence is the problem: in contrast with the Ramble it doesn't allow visitors who in turn cannot become participants as they create a bond with the landscape.

As a challenge to the peasant obsession with productivity, order and plow-schedules the problem with Time Landscape is that the fence is not high enough. It functions as a screen on which urban sub-conscious fears and phobias are projected: 500 year after Robin Hood the outlaws are still hiding in the forest.

|

| Google streetview on Time Landscape. |

vrijdag 24 december 2010

Amazonian (non)art

According to a reviewer on amazon.com 'Arts of the Amazon' (Thames and Hudson, 1995), an overview of the personal collection of Adam Mekler, is THE book on the subject. My copy was remaindered by the Boston Public Library and purchased on ebay for a cheap 10 bucks, but now what? The main part is an excellent text by Peter G. Roe who has the decency to only talk about the objects (pottery, woodcarving, costumes, featherworks) on their own terms, trying to show you how the makers of these things see them. What is art? In this case art are those things some rich fucker can purchase, put on display, in order to feel special and have something interesting to say at parties. The word 'art' has nothing do with these objects whose meaning has no equivalent in our own society. Also see.

woensdag 27 oktober 2010

Cube condensations

Everybody in my little world knows and loves the condensation cube (Hans Haacke, 1963), it is an acrylic plexiglass biosphere of 30 cubic cm and holds about one centimeter of water. “The conditions are comparable to a living organism that reacts in a flexible manner to its surroundings. The image of condensation cannot be precisely predicted. It is changing freely, bound only by statistical limits. I like this freedom.”

It's power is immediate, it was to me and I have only seen the above pic, but why? It has nothing to do with art-world drivel that "the piece may be read as criticism against the closed system of the museum or gallery which attempts to control and contain." It also has nothing to do, as I read somewhere, with the 'fact' that it poses a hard 'question' about screens and surfaces; the Cube as a fivefold surface instead of one as in a painting. No, the power of the Cube is the no-frills directness with which it senses, shows and uses (the condition of ) the envrionment it is in. The simplicity of it can't be beaten, and even if the condensing only works in the controlled circumstances of a museum (??) it wouldn't matter. The Grass Cube (1967) and the Grass Grows (1969) are relevant today for their ecological approach, and when Haacke writes “I’m more interested in the growth of plants - growth as a phenomenon which is something that is outside the realm of forms, composition etc., and has to do with interaction of forces and interaction of energies and information,” he is talking the same language many artists are still using, but the Condensation Cube is not just relevant, it is essential. The Condensation Cube doens't show things, it 'knows' things. In a sense the 'condensation' is already saying too much. I wish the eskimo would exhibit it in an arctic open air artfair...

It's power is immediate, it was to me and I have only seen the above pic, but why? It has nothing to do with art-world drivel that "the piece may be read as criticism against the closed system of the museum or gallery which attempts to control and contain." It also has nothing to do, as I read somewhere, with the 'fact' that it poses a hard 'question' about screens and surfaces; the Cube as a fivefold surface instead of one as in a painting. No, the power of the Cube is the no-frills directness with which it senses, shows and uses (the condition of ) the envrionment it is in. The simplicity of it can't be beaten, and even if the condensing only works in the controlled circumstances of a museum (??) it wouldn't matter. The Grass Cube (1967) and the Grass Grows (1969) are relevant today for their ecological approach, and when Haacke writes “I’m more interested in the growth of plants - growth as a phenomenon which is something that is outside the realm of forms, composition etc., and has to do with interaction of forces and interaction of energies and information,” he is talking the same language many artists are still using, but the Condensation Cube is not just relevant, it is essential. The Condensation Cube doens't show things, it 'knows' things. In a sense the 'condensation' is already saying too much. I wish the eskimo would exhibit it in an arctic open air artfair...

vrijdag 15 oktober 2010

First contact drawing & writing in the Amazon

These are a small number of recorded reactions of people of Amazonia to their first contact with drawing-on-paper and writing. The first question is: what do adults who have never drawn (and who perhaps have never seen pen and paper before and are illiterate) draw and what does it look like?

Here is my collection...

Awi (2000) collects the photos of Michel Pellander, drawings by indians from various tribes and an accompanying text, in Dutch, by Marion Hoekveld. The book does not offer explanations to individual drawings, but one can guess. The following discussion has several noteworthy observations. The translation is mine, the images that follow are wonderful.

Amazonian 'First Contact Drawings' first became prominent with Levi-Strauss' Tristes Tropiques, read the quote below, the pictures of Caduveo face paint are forever etched into every one who has ever seen them.

The following drawings are from Portuguese paper called 'ONISKA: A poética da morte e do mundo entre os Marubo da Amazônia ocidental' (PDF-link) which looks really worthwhile and I wish I could read it. The drawings are probably representations of Marubo cosmology.

The following images are from the Xikrin, (Kayapo village) and were provided by malokeletrika.blogspot.com, who add "Xikrin women are responsible for body painting application to adorn men and women bodies, adults and children, with specific designs depending of sex, age group, ceremonial groups, etcetera. When women are solicited for paint in paper sheets, they reproduce the drawings in the paper sheet, as if that were the human skin. Xikrin men, when asked to draw, produce a large array of spontaneous shapes, from the most figurative to most abstract."

There is little for me to say about these Mehinaku spirit drawings, they are screenshots from Carla D. Stang's 'A walk to the river in Amazonia: ordinary reality for the Mehinaku Indians'.

Joe Kane observed the following on First Contact Drawing by the Waorani but gives no example in his book 'Savages':

Here is my collection...

Awi (2000) collects the photos of Michel Pellander, drawings by indians from various tribes and an accompanying text, in Dutch, by Marion Hoekveld. The book does not offer explanations to individual drawings, but one can guess. The following discussion has several noteworthy observations. The translation is mine, the images that follow are wonderful.

Do indians from the Amazon, when they put pen or pencil to paper for the first time, draw like children? The intense concentration and curiosity to make something appear on paper is similar. The differences lay in experience of age and the experiences of a different environment. Indians usually have no concept of a horizontal line, nor do they have the habit of looking from left to right as you do when reading, nor do they have a concept of top and bottom.

In the first drawings of the Arara the beginning is often the centre, from which the paper is filled circling from the inside to the outside. A picture they can study with similar intent while they keep it upside down; the rotation of the image does not seem to make a difference. The straight line is the first thing they learn.

To draw is to communicate. To capture an animal on paper is to draw everything which is there in reality, to give him two eyes even when he is drawn sideways. De Arara sometimes make a kind a X-ray drawings. They draw that what can't be seen, the bones inside an animal. The Yanomami draw their spirits, the upper world, the nether world, the rain, the thunder, but also the goldminers. They also draw sky maps, stars, and the moon. Stars are actors in myths of origin and they offer clues on time, direction, seasons, on agricultural cycles. Slowly Waiwai draws his territory. In his mind he follows rivers and tracks. De leaders of the Waiapi can draw cartographic maps; they have been involved in the demarcation of their territory and know every minute detail of it.

They also draw decorative motives: butterflies, turtle shields, snakes, fishbones, They have become abstracted. Ornament always refers to nature, they always have meaning. They are turned into patterns, on the skin, on earthenware pots, on wooden benches. In this way drawing has meaning.

Slowly but concentrated Kamaratxia Awa is drawing on paper, his thoughts seem to run through his felt pen, his hand freely above the paper. When he begins to draw, only after he has examined the pens very carefully, a world starts to appear which suggests am enormous ordered and controllable space. A world which is created from scribbles and dots.

|

| By Karhitxia Awa |

|

| By Karhitxia Awa |

|

| By Werena Waiapi |

|

Amazonian 'First Contact Drawings' first became prominent with Levi-Strauss' Tristes Tropiques, read the quote below, the pictures of Caduveo face paint are forever etched into every one who has ever seen them.

That the Nambikwara could not write goes without saying. But they were also unable to draw, except for a few dots and zigzags on their calabashes. I distributed pencils and paper among them, none the less, as I had done with the Caduveo. At first they made no use of them. Then, one day, I saw that they were all busy drawing wavy horizontal lines on the paper. What were they trying to do? I could only conclude that they were writing or, more exactly, that they were trying to do as I did with my pencils. As I had never tried to amuse them with drawings, they could not conceive of any other use for this implement. With most of them, that was as far as they got: but their leader saw further into the problem. Doubtless he was the only one among them to have understood what writing was for. So he asked me for one of my notepads; and when we were working together he did not give me his answers in words, but traced a wavy line or two on the paper and gave it to me, as if I could read what he had to say. He himself was all but deceived by his own play-acting. Each time he drew a line he would examine it with great care, as if its meaning must suddenly leap to the eye; and every time a look of disappointment came over his face. But he would never give up trying, and there was an unspoken agreement between us that his scribblings had a meaning that I did my best to decipher; his own verbal commentary was so prompt in coming that I had no need to ask him to explain what he had written.

And now, no sooner was everyone assembled than he drew forth from a basket a piece of paper covered with scribbled lines and pretended to read from it. With a show of hesitation he looked up and down his list for the objects to be given in exchange for his people s presents. So-and-so was to receive a machete in return for his bow and arrows, and another a string of beads in return for his necklaces and so on for two solid hours. What was he hoping for? To deceive himself perhaps: but, even more, to amaze his companions and persuade them that his intermediacy was responsible for the exchanges. He had allied himself with the white man, as equal with equal, and could now share in his secrets.

The following drawings are from Portuguese paper called 'ONISKA: A poética da morte e do mundo entre os Marubo da Amazônia ocidental' (PDF-link) which looks really worthwhile and I wish I could read it. The drawings are probably representations of Marubo cosmology.

The following images were used as illustrations in "Xingu, the Indians, their Myths", a 1970 book of Amazonian myths collected by Orlando and Claudio Villas Boas. The drawings are made by Wacupia. Kenneth S. Brecher in the foreword to the English edition tells us many relevant details about this First Contact Drawing-maker

The drawings which illustrate this book were done by a Waura tribesman called Wacupia, who using pen and paper for the first time, produced a fascinating record of the animals, spirits, and material culture of the Alto-Xingu. The drawings were done over a period of several months and in secret, as Wacupia feared they they might be interpreted as witchcraft by the rest of the tribe. The Xingu tribes paint their bodies and certain material objects in highly symbolic geometrical patterns, but they would have no interest in or occasion for drawing as a means of record or pleasure. The Waura do frequently resort to witchcraft, and I believe that Wacupia was very interested to see if he could [...] employ drawing as a means of reviving the dead or gaining control over the spirit of the object in question.

There is little for me to say about these Mehinaku spirit drawings, they are screenshots from Carla D. Stang's 'A walk to the river in Amazonia: ordinary reality for the Mehinaku Indians'.

The First Contact Drawing image below is one of my favourites. It belongs to the following passage from Algot lange's "The lower Amazon; a narrative of explorations in the little known regions of the state of Pará, on the lower Amazon" (1914). What I like about it is that it is a map, so it should go here.

The sun now is setting; not a sound is heard in the maloca except some japlm birds chirping around their suspended nests, and a couple of arara parrots which are roosting in the tall Brazilnut tree at the end of the maloca. Otherwise all is silent. I am pleased to see for the first time a couple of these parrots at rest and "at home."

I find this is the best hour to record my observations of the day as only the old chief has enough patience to sit by my hammock to bother me. He watches intently the movements of the pencil over the paper and now and then he points at some word, looks at me grinning, and says something. I give him the pencil and my note-book. He seizes the pencil awkwardly and after some minutes returns it. He has tried to imitate handwriting and feels proud (sec page of note-book). Then he asks smilingly for the book again and draws some more, shows me the drawing, and ejaculates Kari Katu Kuyamhira (Good white relative). This is the figure marked "A" on the right of the illustration. The scrolls represent his idea of the surrounding forest. Old Tute also joins in these attempts at writing longhand and his effort is presented on the same sheet.

Joe Kane observed the following on First Contact Drawing by the Waorani but gives no example in his book 'Savages':

Miniwa spoke no Spanish, but he was, as near as I could tell, absolutely without fear. His gaze was so penetrating, so intense, that whenever it came to settle on me I felt very much as if he intended to "hunt you like a wild pig." ... One day he reached down, yanked my pen out of my hand, and, gripping it like an ice pick, drew on the page. He made a series of half circles, opening first one way, then the opposite way, back and forth. When he finished he pointed to one of them and said a whole lot of things, of which I caught only one word: Menga. It would be weeks before I understood that Miniwa had drawn a map. The half circles represented watersheds, with creeks and rivers running one way, then another. In the middle, at the biggest divide, we would find Menga: still on the ridge, still, for all intents and purposes, beyond contact.Dan Everett adds the following on the Pariha in his book 'Don't sleep there are snakes':

The Pirahas would 'write stories' on paper, which I gave them for this purpose at their request. These inscriptions consisted of a series of identical, repetitive, usually circular marks. But the authors would 'read' their stories back to me, telling me something about their day, about someone's sickness, and so on - all of which they claimed to be reading from their marks. They might even make marks on paper and say Portuguese numbers, while holding the paper for me to see. They did not care at all that their symbols were all the same, nor that there are such things as correct and incorrect written forms. When I asked them to draw a symbol twice, it was never replicated. They considered their writing to be no different from the marks that I made. In classes, we were never able to train a Piraha to draw a straight line without serious 'coaching', and they were never able to repeat the feat in a subsequent trials without more coaching. Partially this was because they see the entire process as fun and enjoy the interaction, but it was also because the concept of a 'correct' way to draw things is profoundly foreign.

There is of course only one proper art of the Amazonia and that's bodypaint, all are taken from this excellent French blog.

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)