Gardens, gardening and forestry in the Amazon:

Listen to Phillipe Descola:

For the Achuar view the forest, with its bewildering diversity of plants, as a sort of gigantical botanical garden meticulously tended by Shakaim, a timid and unprepossessing spirit. This segment of the world which evolves and develops independently from human norms, and that we usually call nature, is not for the Achuar a mere object to be socialized, but the ubiquitous subject of social relations.

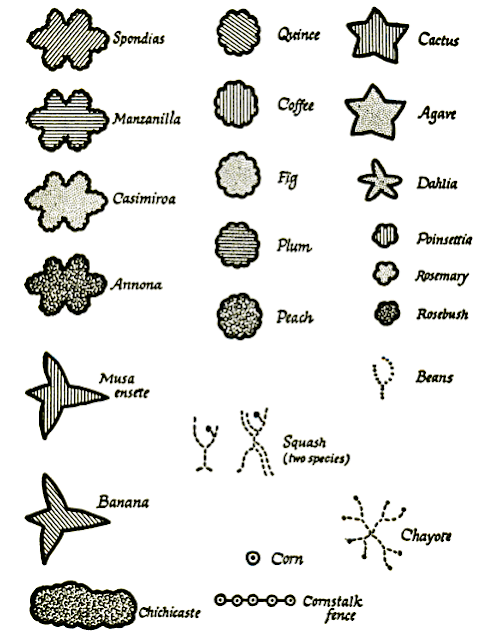

From 'Plants, man, and life' (1967) by Edgar Anderson, images above:

"The garden I charted was a small affair about the size of a small city lot in the United States. It was covered with a riotous growth so luxuriant and so apparently planless that any ordinary American or European visitor, accustomed to the puritanical primness of north European gardens, would have supposed (if he even chanced to realize it was indeed a garden) that it must be a deserted one. Yet when I went through it carefully I could fine no plants which were not useful to the owner in some way or another."

Listen to Ezra Pound:

The weeder is supremely needed if the Garden of the Muses is to persist as a garden.

Listen to Michael Williams (Deforesting the earth: from prehistory to global crisis):

An important factor in the domestication process was defecation. The seeds of sweet-corn, tomatoes, lemons, cucumbers, and many more edible plants, as well as fruits of shrubs and trees, can pass intact through the human as well as the animal gut (it may even enhance their reproductive vigour), and can be subsequently dispersed and reproduced. In the case of humans the peripheral latrine areas common to virtually all societies would become new gardens in time

Listen to Michel Conan (Perspectives on garden histories):

Many anthropologists working in the Amazon Basin have been struck by the resemblance between gardens and the forest. Fifteen months after the forest has been cleared, Achuar gardens have reached their grown-up appearance, and their three-tiered levels of foliage reproduce on a smaller scale and in rather orderly fashion the surrounding forest. Larger-leafed banana trees and papaya trees provide the top cover, cassava plants contribute the larger part of the second cover that prevents the earth from being washed out by rain, and different vegetables and smaller plants provide ground cover. Thus gardens appear as a cultural imitation of the natural forest. One of the most arresting results of the method used by Descola is that it enabled him to show that this is only true to the eye of a Western observer. Actually for the Achuar, the forest is just another garden that is cared for by the spirits who are almost human (they take care of the wild animals as humans do to their own tame animals, and they hunt them in order to eat them as humans do their poultry). He has shown that nature is organized according to social relationships that are identical to social relationships within the household. Nature is perceived along a pattern derived from household life in Achuar society. It turns out that social relationships within their society provide the models for describing nature, rather than nature providing the model for social relationships and artifacts as we would have it.

Listen to Darrell Addison Posey on Kayapó gardening:

Another of the major misconceptions about slash-and-burn agriculture is that fields are abandoned to fallow after two or three years because the soil loses its fertility, and weeds and insects take over. Loss of fertility of the soil, however, is not the factor that determines that agriculture takes a shifting pattern.

Soil analyses shows that the soils are not exhausted after two or even three years. Furthermore, soils are totally rejuvenated after 10-12 years of fallow. Yet no Kayapó field in Gorotire in replanted in less than 15-20 years. Kayapó Field plots in most cases are scattered three to four hours' journey away from the village, although suitable, adequately fallowed, old plots might be only 15-20 minutes away. The Kayapó ordinarily seek to minimize effort and work so that this seems to be a great inconsistency in their cultural pattern.

The Kayapó recognize that the high forest is relatively sparse in animal life, while forest clearing furnish habitat for smaller leafy and bushy plants that attract wildlife. They know that leaving 'abandoned' fields to the natural reforestation sequence artificially creates domains that stimulate wildlife populations. They also know that the more widely their 'abandoned' fields are dispersed, the greater the area available to attract game - and the easier the hunting. Dispersed fields also naturally limit viral, fungal, and insect crop pests.

This sensitivity to forest succession explains why the Kayapó are willing to let close-by old fields remain fallow. Although it might be easier to replant nearby fields more frequently, it would just mean having to go further away to hunt for game and for the essential gathered products from the secondary forest.

|

| Yanomami on the trail |

Listen to Darrell Addison Posey on nomadic agriculture:

Although ‘settled’ for several decades now, the Kayapó have not deserted their semi-nomadic habits entirely. They spend several months each year in the Brazil nut groves living in communal houses; go on frequent collecting and hunting trips; and before major festivals make two- or three-week treks to acquire ceremonial game and feathers.

The Kayapó have never left everything on their journeys to chance, however, but have developed an interesting ‘nomadic agriculture’, which they continue to use today.

While routinely scavenging about the forest, the Indians gather dozens of plants, carry them back to the forest campsites or trails, and replant them in natural forest clearings. The plants include several types of wild manioc, three varieties of wild yams, a type of bush bean, and three or more wild varieties of kupa.

These forest fields are always located near streams, which generally guarantee a stand of trees. Even in the savanna, where patches of forest are often few and far between, there are areas where collected plants have been replanted to form food depots.

The Kayapó once maintained an extensive system of interlacing trails linking all their vast territory. Most of these ancient trails are now abandoned, but not all, and the Kayapó are still masters of the forest and savanna and travel considerable distances.

I once traveled for five days with four Kayapó man on long-abandoned trails to an ancient village site. Although the trails were overgrown and difficult to follow, they had been used so much that in some places they were etched six inches into the hard earth. Each night we would stop at a stream in some spot flattened and hardened by years of use. The men would slip off into the forest and soon return with a variety of roots, tubers, stalks and fruits. Foods were readily acquired even on parts of the trail known to have been abandoned 40 years before.

It was nearly two months after I began my life with the Kayapó that I realized that not all collected roots, seeds and cuttings ended up in stomachs. For example, a Kayapó would find it natural to replant a portion of what he had foraged near where he defecated.

|

| Surui Reforestation |

Listen to Darrell Addison Posey on Kapayo ecosystem engineering:

The creation of forest islands, or Apete, demonstrates to what extent the Kayapo can alter and manage ecosystems to increase biological diversity. Apete begin as small mounds of vegetation, about one to two meters round, created by ant nests in open areas in the field. Slight depressions are usually picked out because they are more likely to retain moisture. Seeds or seedlings are planted in these piles of organic material. The Apete are usually formed in August and September, during the first rains of the wet season, and then nurtured by the Indians as they pass along the savannah trails. As Apete grow, they begin to look like up-turned hats, with higher vegetation in the centre and lower herbs growing in the shaded borders. The Indians usually cut down the highest trees in the centre to create a donut-hole centre that allows the light into older Apete. Thus a full-grown Apete has an architecture that creates zones that vary in shade, light and humidity. These islands become important sources of medicinal and edible plants, as well as places of rest. Palms, which have a variety of uses, prominently figure in Apete, as do shade trees. Even vines that produce drinkable water are transplanted here. Apete look so "natural", however, that until recently scientists in fact did not recognise them as human artefacts. According to informants, of a total of 120 species inventoried in ten Apete, about 75 percent could have been planted. Such ecological engineering requires detailed knowledge of soil fertility, micro-climatic variations, and species niches, as well as the interrelationships among species that are introduced into these human-made communities.

|

| Forest Island Boliva |